Recently I experienced my first professional development day. I’ve been led to believe that PD’s can be pretty hit or miss… usually more miss. Luckily, we had a fabulous and important training from Missy and Nic at the Masschusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s Safe Schools Program. The Safe Schools Program for LGBTQ Students “provides training, technical assistance, and professional development to school administrators and staff on topics related to gender identity, sexual orientation, and school climate” (DESE).

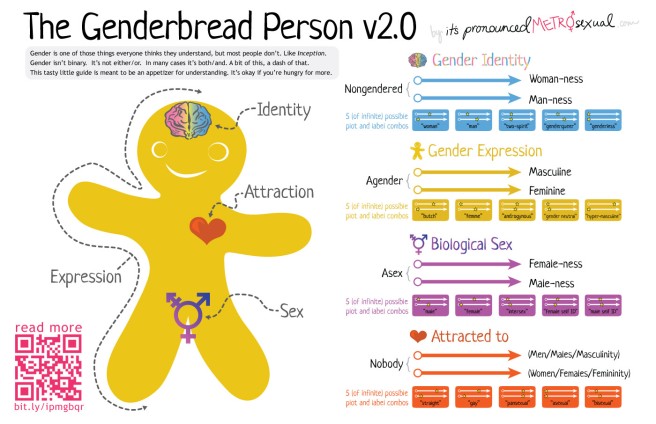

They talked with us for a full two hours about what it means to create a safe, welcoming school environment for LGBTQ students. We discussed topics like gender identity, sexual orientation, and biological sex at birth, and the differences among the three. But before speaking with us, Missy and Nic had previously spoken with some of the student leaders of the LGBTQ population at the school about who among the faculty and administration they felt to be allies and why.

So what does it mean to be an ally? Well, according to our student leaders, it means first and foremost being willing to speak up about being an ally. Students most trusted faculty whom they felt respected them, had their backs, and talked openly about issues of gender identity and sexual orientation. In some ways, being an ally means naming yourself as an ally, so students know they can come to you when they need to.

LGBTQ students also consider teachers allies when they inquire about and do their best to abide by students’ chosen pronouns and/or names. It’s a small linguistic adjustment, to refer to someone by their chosen pronouns, but Nic spoke passionately about how much it means to him when people make the effort, and how hurtful it can be when they get it wrong, even inadvertently.

And finally, Missy and Nic touched on how important it is to not violate a student’s privacy, whether in speaking to another faculty member, another student, or that student’s parents or guardians. As teachers, we should always assume that what we discuss with an LGBTQ student is confidential (barring any other concerns for health or safety) and not share it with others without that student’s consent.

Our conversation was rich, deep, and covered a lot more ground than that. But even these three points will significantly impact my teaching. I want to name myself, now and in the future, as an ally to my LGBTQ students. I’ll discuss issues that matter to queer teens in my classroom — literature lends itself particularly well to those conversations. I’ll also post a safe zone sticker, like the one pictured here from HRC, somewhere visible in my classroom. (They do matter; our students could name every faculty member that had one posted.) When I meet students for the first time — say, at the beginning of the school year — I’ll make sure to invite each one to share, if they’re comfortable, their chosen pronouns and names. And if, as I hope, my queer students will trust me enough to share with me, I’ll honor their trust by keeping what’s said between us private.

Because I’m an ally.

P.S. The MA DESE website has a thorough listing of resources on this subject for teachers, as does the website of Jeff Perrotti, who created the Safe Schools MA program.

UPDATE [2/21/16]: My friend and colleague Anne Mooney has posted her own marvelous discussion of how and why to introduce preferred pronouns and the grammatical acceptability of the singular “they” based on this same PD. Check it out over at Habits of ELA.